CBP vs. Forest Prime Evil

Photo courtesy USDA

What would you say is the most serious threat to our nation’s forests? Wildfires? Logging and timber industry interests? Urban sprawl and development?

It’s actually something smaller than a paper clip. It’s an insect.

Make that insects – specifically, non-native, invasive wood-boring beetles such as the emerald ash borer and the Asian longhorned beetle. Insects actually destroy more timber each year than wildfires, but because they quietly do their damage to small, isolated stands of trees in remote areas, they don’t make the headlines like more photogenic wildfires.

Customs and Border Protection agriculture specialists are responsible for intercepting these wood-boring pests at U.S. ports of entry. Currently, agriculture specialists work at 167 sea, air and land ports of entry. Their mission is preventing the entry of invasive plants and foreign animal diseases.

Some cargo entering the U.S., whether at a land, sea or air port of entry, is packed on or in wood packaging material. This material is subject to rules and regulations that require it to be treated to prevent pest infestation.

Agriculture is the largest industry and employer in the U.S., with more than $1 trillion in annual economic activity. Invasive species have caused $138 billion annually in lost agriculture revenue, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Native insects – even those that feed on trees, such as the mountain pine beetle – are valuable sources of food for birds and other wildlife.

Non-native pests – often referred to as invasive – pose an increased threat because they have few natural predators. Native bird populations have not developed a taste for, say, the Asian longhorned beetle and are not likely to do so for thousands of years. Mother Nature takes her sweet time when it comes to evolution.

The Invaders

Of the eight families of wood-boring pests, Cerambycidae (longhorn) and Buprestidae (metallic wood-boring) beetles are especially destructive because they bore deep into the centers of trees and are thus more difficult to detect and eradicate.

| Wood Packaging Materials Pests of Concern | |

|---|---|

| Latin Name | Common Name |

| Buprestidae | Metallic beetles |

| Cerambycidae | Longhorned beetles |

| Cossidae | Carpenter moths and leopard moths |

| Curculionidae | Bark weevils |

| Platypodidae | Pinhole borers |

| Scolytidae | Bark beetles (most common interception) |

| Sesiidae | Clearwing moths |

| Siricidae | Wood wasps |

Source: USDA and CBP

Probably the most dangerous wood-boring pest is the Asian longhorned beetle (Anoplophora glabripennis). This beetle is native to eastern China, Korea and Japan. It was accidentally introduced into the U.S. in the 1980s – most likely on wood packaging material holding plumbing supplies from China that was sent to a warehouse in Brooklyn, New York. From there, infestations were eventually reported in New Jersey and upstate New York.

In 1998, the Asian longhorned beetle was spotted in Chicago; in 2005, two adult specimens were found outside of a warehouse in Sacramento, California. Since then, there have been several reported in Massachusetts and one reported sighting in Ohio.

The emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis) is another invasive pest. It is native to Asia and Eastern Russia, and it was first found in America in June 2002 in Michigan. It, too, was probably brought into the U.S. unintentionally in ash wood dunnage, which stabilizes cargo during shipping. The emerald ash borer can also travel via the movement of firewood and nursery tree stock.

Unlike the Asian longhorned beetle, however, the ash borer feeds only on ash trees. The adult beetles attack ash foliage but cause little damage. The larvae (the immature stage) are far more dangerous, creating tunnels or “galleries” inside the trees’ inner bark, disrupting their ability to transport water and nutrients.

The Asian longhorned beetle typically does not disperse more than a few hundred yards from where it hatches. However, the emerald ash borer is a robust flier, capable of immediate flight upon emerging from the host tree and able to cover distances of up to a half mile at a time.

By the time both of these pests are detected in trees, the damage is usually irreversible. Typically, the tree will be dead within several years.

A tree-lined street in Toledo, Ohio, in 2006, and the same street three years later, showing the destructive effects of the Emerald ash borer. Photo by Daniel A. Herms, Ohio State University

The Stakes

The U.S. is the largest exporter of wood in the world. Annual production is more than 30 billion board feet, making the U.S. the largest producer and consumer of lumber. (In the lumber industry, one “board foot” equals the volume of a one-foot length of a board that is one foot wide and one inch thick.)

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, the U.S. boasts 232,592,650 acres of forest and the U.S. timber industry is a $1 billion annual market. The timber industry employs more than 80,000 workers in the sawmill and wood preservation industries, while another 230,000 Americans directly depend on sawmills for their employment.

The Asian longhorned beetle infests 24 species of hardwood trees, primarily maple, willow and elm. Adults feed on healthy bark as well as trees’ interiors, typically destroying each tree from the inside out and making the eradication of the beetle larvae nearly impossible.

A study by the USDA Forest Service estimates that if the Asian longhorned beetle becomes established, it could destroy 30 percent of all urban trees – as many as 1.2 billion trees – for a loss of as much as $669 billion.

More than 1,500 trees in Chicago were cut down as part of the eradication process in that city, which took 10 years and cost $70 million. In many areas, surrounding stands of healthy trees have been removed to prevent further spread of the pest. In New York, more than 6,000 infested trees resulted in the removal of 18,000 healthy trees. The story is much the same in New Jersey, where an infestation of 700 trees led to the purposeful destruction of nearly 23,000 trees.

This beetle is so destructive that in China it has damaged approximately 40 percent of poplar plantations, rendering the wood suitable only for packaging material. More than 50 million trees were destroyed over a three-year period in just one Chinese province because of Asian longhorned beetle infestations.

That destruction occurred in a country that harbors natural predators that can keep the beetle populations in check. The situation would be far worse here. If the Asian longhorned beetle becomes established in the U.S., it could eventually destroy 1.2 billion trees – roughly one-third of all U.S. trees.

Quarantines around infested U.S. areas prevent the accidental spread of the pest by people who transport firewood or dispose of downed trees and limbs. Infested trees are removed, chipped in place, and the chips are burned to destroy all stages of the insect’s life cycle, and stumps are ground to below the soil level.

As for the emerald ash borer, there are approximately 8 billion ash trees in the U.S. In mid-2002, scientists suspected that widespread damage to ash trees in southern Michigan – particularly in and around Detroit – was caused by the ash borer. Even worse, the pest was believed to have been established in Michigan for at least 10 years by the time of its discovery.

As of 2011, over 50 million trees have been cut down due to emerald ash borer infestation. The pest has spread to 22 states in the U.S. and two provinces in Canada. Most states have placed quarantines on infected areas by prohibiting the transport of ash nursery stock, ash timber products and ash firewood.

The Transport

Wood packaging material is wood or wood products (excluding paper products) that support, protect or carry a commodity. It is primarily pallets, but also includes dunnage.

Compared to plastic and metal, pallets and other packaging material made from wood are plentiful and cheap. Most pallets can carry up to 1 ton of cargo. The U.S. produces more than half a billion pallets each year, and about 2 billion pallets are in use across the nation at any given time.

Proponents of plastic pallets argue that using wood to make pallets and other packaging materials contributes to deforestation, helps the spread of invasive pests, and requires chemical or heat treatments to kill insects and pathogens. They also note that plastic pallets benefit the environment by reducing the amount of fuel needed to transport goods because each plastic pallet typically weighs as much as 50 pounds less than its wooden counterpart.

Nevertheless, wood continues to outpace the demand for other materials in the pallet market. Wood is cheap, plentiful, easy to repair, biodegradable, and more easily recyclable into mulch, paper or poster board. According to the most recent pallet user survey conducted by Modern Materials Handling magazine, wood continues to dominate the pallet market, with 95 percent of respondents reporting that they use wooden pallets at their facility.

All this wood is irresistible to wood-boring insects. They consume the wood, and their excretions – called frass – are telltale signs of infestation in shipping containers and on or near wood packaging materials.

The rising volume of trade means that there are increasing opportunities for wood-boring pests to gain entry to the U.S. Because of the wood borer infestations in the 1990s, the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service finalized its import regulations for wood packaging materials in 2004 to require these materials from all countries to be chemically treated (usually with methyl bromide) or subject to heat treatment, such as being placed in a kiln to be dried.

Today, wood packaging materials entering the U.S. must bear a special marking – called an International Plant Protection Convention, or IPPC, certification symbol – proving that it has been treated. The International Plant Protection Convention is an international treaty to prevent the spread of pests that attack plants and plant products. Recognizing the potential problem, other nations have adopted similar measures.

The IPPC adopted the International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures, known as ISPM 15, in 2004. These standards require wood packaging material to be either heat-treated or fumigated to rid the material of dangerous pests.

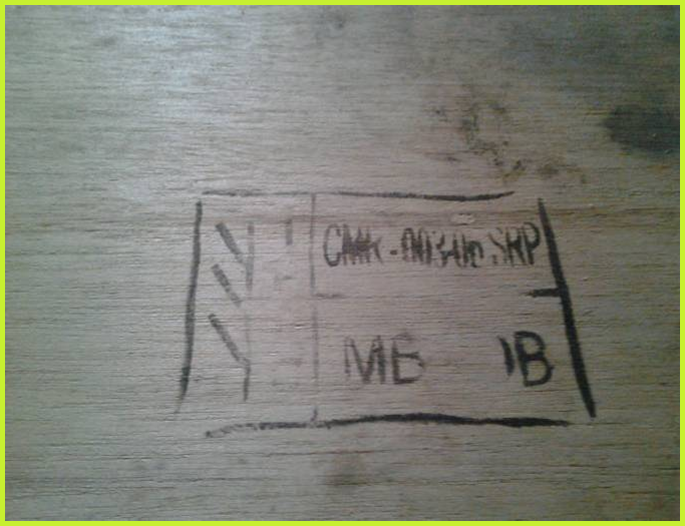

To comply with these standards, wood packaging material must be marked with the IPPC symbol in a visible location on each article, preferably on at least two opposite sides of the article, with a legible and permanent mark. This IPPC mark is known colloquially as a “wheat stamp.”

Products that are exempt from ISPM 15 standards are made from paper, plastic or wood panel products, such as particle board and plywood.

Some shippers who want to avoid the time and effort it takes to have their wood packaging materials properly treated have been known to get creative, hand-drawing the IPCC stamp on the wood packaging materials.

For companies that export to the U.S., compliance with the ISPM 15 rules is of paramount importance. Wood packaging material that does not bear the ISPM 15 stamp must be re-exported (sent back to its country of origin) immediately, usually with the associated commodity itself. Even if the material has the proper markings, it must be re-exported if it contains a wood-boring insect. If that insect poses an immediate risk of introduction, e.g., if it’s an emerging adult, the shipment may need to be fumigated prior to re-export

This all results in lost revenue and costly delays for both the exporter and for the U.S. importer seeking to use or resell the commodity.

The Cargo

The commodities with the highest incidence of wood packaging material pest interceptions are metal and stone products (including tile), machinery (such as automobile parts and farm equipment), electronics, bulk food shipments and finished wood articles.

In fiscal year 2012, the top five ports to first receive shipments with non-compliant wood packaging materials were Laredo, Texas; Pharr, Texas; Blaine, Washington; Long Beach, California; and Romulus, Michigan. The top five did not change appreciably during fiscal year 2013. Blaine, Laredo, and Pharr continue to top the list, with Brownsville, Texas, and Houston bringing up the rear.

That is because approximately half (48 percent) of the total national non-compliant wood packaging material shipments originate in Mexico. China is second to Mexico as the leading source of non-compliant wood packaging material shipments, followed by India and Germany.

For example, a 2014 shipment of fresh corn arrived at the Nogales port of entry in Arizona. A CBP agriculture specialist found eight immature Scolytidae sp., in wooden pallets bearing the pre-treatment certification stamp. Scolytidae are a family of bark beetles that includes the mountain pine beetle – but also the European elm bark beetles, which can transmit Dutch elm disease fungi. The corn was shipped back to Mexico.

The list goes on:

At the Los Angeles/Long Beach seaport a CBP agriculture specialist examined a shipment of shotguns from Turkey and noticed tunnels called “galleries,” and insect excrement – called “frass” – throughout the wood packaging. The specialist split open a piece of wood and found a larva identified by the USDA as Asian longhorned beetle. CBP instructed the importer to re-export the shipment.

At the land border port of entry in International Falls, Minnesota, a CBP agriculture specialist inspected a shipment of auto parts from China and found wood-boring insects in the packaging material. The USDA identified one live adult specimen as Curculionidae, a Japanese weevil. The shipment was refused entry and re-exported.

A commercial shipment of laser printer toner cartridges, destined for Kentucky, was inspected at the El Paso, Texas, port of entry. A CBP agriculture specialist discovered three live adult wood-boring pests in a pallet. The shipment was re-exported to Mexico.

In Seattle, a CBP agriculture specialist inspected a shipment of Turkish porcelain tile, destined for Texas, and discovered a live beetle larva in the stamped wood packaging material. The USDA identified the insect as metallic beetle, and the tiles went back to Turkey.

The Specialist

CBP Agriculture Specialist Miguel “Mike” Garcia was teaching seventh-grade biology when 9/11 changed America and its borders forever.

“I had wanted to be a physical therapist and possibly become a doctor, and I even trained as a PT technician in college,” Garcia recalled. “But I went into teaching, and after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks I thought about joining Border Patrol.”

Garcia’s brother-in-law, who was an IT specialist for the USDA at the time, tipped him off to opportunities at the agency, and Garcia joined the Plant Protection and Quarantine division of USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. Garcia and many of his colleagues transitioned to become CBP agriculture specialists.

All CBP agriculture specialists must possess a bachelor’s or higher degree with a major in biological sciences or a combination of experience and education that includes 24 semester hours in biological sciences. New recruits must successfully complete 10 to 12 weeks of training at the USDA’s Professional Development Center, which has trained agriculture specialists since the inception of CBP in 2003.

“Our agriculture specialists work very hard to protect our natural resources and American agriculture” said Mikel Tookes, deputy executive director for the CBP Office of Field Operations Agriculture Programs and Trade Liaison. “We are vigilant, talented and dedicated to our mission.”

Garcia spent seven months at the cargo lot in Pharr, Texas, where he said it was easy to spot insects. “Pharr was a lot of work because the volume of produce, machinery, all kinds of cargo on pallets that come through port is just huge. You can pretty much find bugs everywhere,” Garcia said.

Garcia became adept at spotting bugs. During his rookie year as an agriculture specialist, his talents for finding six-legged stowaways earned him a Blue Eagle award. “I found an Anastrepha – a Mexican fruit fly – in a truck bed, so we sent the truck back. Two weeks later, we found another. At this point, we started checking everything. And we narrowed the problem down to manzano peppers that were coming out of a particular warehouse.” He figures that solving that little problem may have saved as much as $1 million for U.S. farmers who were spared the trouble of dealing with the destructive creatures.

Garcia currently works at the Veterans International Bridge in Brownsville, Texas, and he continues to hone his skills and talents on wood packaging and pallet inspections.

And there are a lot of pallets. Laredo is just across the border from an area of Mexico that has numerous maquiladoras – factories that import material and equipment on a duty-free or tariff-free basis to produce everything from auto parts and apparel to electronics, furniture, and appliances. Mexico’s 3,000 maquiladoras account for half of Mexico’s exports, and the trucks keep coming, all day, every day.

Garcia has proven to be so good at detecting and removing wood-boring insects that he quickly earned a nickname: the Beaver.

“You can find bugs everywhere,” Garcia said. “You just have to know where to look and what to look for.” Garcia’s training has paid off. For example, he has intercepted many beetles from Russia that are in the same family as the Asian longhorned beetle.

Garcia’s talents aren’t limited to wood-boring pests. He also has intercepted other highly destructive invasive pests, including Asian gypsy moth and Mexican fruit fly. He also stopped a pest called a melon thrip – Thrips palmi Karny – while inspecting a shipment of eggplants from Mexico. It was the first time this pest had been intercepted on the U.S.-Mexico border. The melon thrip feeds on a wide range of ornamental plants and crops and can be vectors of plant viruses.

The most challenging aspect of his work, according to Garcia, is educating brokers about the importance of making sure their trucks and pallets are pest-free. “That, and the paperwork,” Garcia said with a smile.

The Scientist

en·to·mol·o·gy

/ [en-tuh-mol-uh-jee]

noun

the branch of zoology dealing with the study of insects.

A fair share of many CBP agriculture specialists’ paperwork finds its way to Dr. Steven W. Lingafelter. He is a research entomologist for the USDA Research Service, based at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

He has been studying insects his entire life. “I have had a lifelong interest in biology and I always collected insects as a kid,” Lingafelter said. “Initially, I was going to be a veterinarian until I realized I could also get a job as an entomologist.”

Lingafelter earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Midwestern State University (Wichita Falls, Texas) and a doctorate from the University of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas) and, like many scientists, he peers into his fair share of microscopes.

But at the Systematic Entomology Laboratory he begins his workday pretty much like most people: returning phone calls and fielding emails. Those duties are usually followed by a few hours working on various research papers.

By late morning, the fun begins.

“The first of my identification lots arrive – these are specimens intercepted by CBP agriculture specialists at ports of entry around the country, usually found in cargo or in passengers’ luggage,” said Lingafelter.

But wait times don’t just affect travelers and cargo; insects have to take a number in Lingafelter’s lab. “I often have too many identifications to keep up with,” he said. “The specimens come in from all over the country, from CBP ports of entry as well as from university scientists and agricultural extension offices.”

Lingafelter oversees the largest collection of wood-boring beetles outside of Europe, so he receives daily requests for identifications from all over the world. “Most of these involve looking at specimens, sending loans, getting literature, etc. It is very difficult to stay on top of this and maintain a strong research output,” he said.

Lingafelter and his colleagues are acutely aware of the importance of their identifications, because cargo is not permitted to proceed into the country until the specimens are identified to prevent the potential introduction of invasive or destructive species.

“I enjoy working with specimens and making determinations of their species or, in some cases, determining that they are new to science and need formal descriptions,” he said. “The incredible diversity of beetles is what makes my job exciting. Every day I see something new or rare.”

It can be painstaking work. “The identifications can take a few hours,” Lingafelter noted. In the afternoon, if time permits, Lingafelter tackles more research and, as the editor of two scientific journals, he also reviews papers submitted by others. He oversees the cataloguing and storage of specimens and provides occasional tours to visiting scientists and students who want to study his processes.

His collection is vast, and it has been in the works for decades. The Smithsonian’s first wood-boring insect specimen dates from the 1860s. On the 10th floor of a building recently constructed in a former courtyard inside the Smithsonian’s Natural History Museum, Lingafelter and his colleagues toil in a ring of offices that surround row after row of tall metal lockers – each of which can hold as many as 30 cases of specimens. Each case can contain dozens of insects, all meticulously mounted on pins and labeled.

As an entomologist, Lingafelter’s area of expertise is beetles – particularly the families Cerambycidae and Buprestidae. “My two research families include the Asian longhorned beetle and the emerald ash borer,” he explained. “These two very important pests have gotten the attention of the U.S. forestry and timber industries recently.”

And for good reason. Wood-boring insects can decimate entire forests.

“The number one [agriculture] concern at the border should be to keep out invasive pests,” Lingafelter said. “Any wood-boring or plant-feeding species – regardless of whether it poses a problem in the native country or not – has the potential to be a major and costly pest here in the U.S.” Entire ecosystems could change because there are no natural predators or diseases here to keep these pests’ numbers in check.

“The Asian longhorned beetle is a perfect example of a species that attacked many more hosts than previously known for the species,” Lingafelter explained. “This pest radiated out from the introduction points in New York and Chicago, infesting many available trees. The only way to eradicate or control them was to destroy all trees that showed any evidence of infestation. This was, and is, a very costly and extreme measure, but it is necessary to prevent further spread.”

The other major groups of wood-boring pests are scolytides (considered now as a subfamily of weevils). These small beetles can build up immense populations. “Scolytides can have periodic outbreaks that can kill thousands of acres of pine trees, making large tracts of forest very susceptible to forest fires,” Lingafelter noted. “Some species can transmit Dutch elm disease, which has devastated the North American elm population.”

Some observers have proposed careful introductions of these insects’ natural predators from their native countries. But Lingafelter and other scientists warn that the intentional introduction of non-native predators to control those invasive species would need to be done with extreme caution.

“Just as we don’t know the full ramifications of an invasive species, with regard to what new hosts it will infest, we don’t know exactly how a predator will behave,” he pointed out. “Perhaps the predator will attack other native, potentially beneficial insects. History is riddled with failed examples of intentional importation of predators.”

Lingafelter cited the example of the cane toad in Australia, which was intentionally imported to control the sugar cane beetles and which then resulted in the destruction of many native animals because of the toad’s toxins.

“CBP agriculture specialists are vital to protecting our timber resources from the potentially devastating impacts that these invasive pests could have on our forests,” Lingafelter observed.