Immigration Special Agent Confronts Human Trafficking in 1914

One hundred years ago and before American women could vote, Kate Waller Barrett was named special agent for the U.S. Bureau of Immigration to investigate one of the most notorious issues of the day – international human trafficking. Barrett was sent abroad not only on a fact-finding mission, but also to secure cooperation of foreign governments and international non-governmental organizations in combating trafficking and aiding its victims. Her efforts addressed both the roots and humanitarian issues related to human trafficking, as well as improved employment opportunities for women within the U.S. Bureau of Immigration.

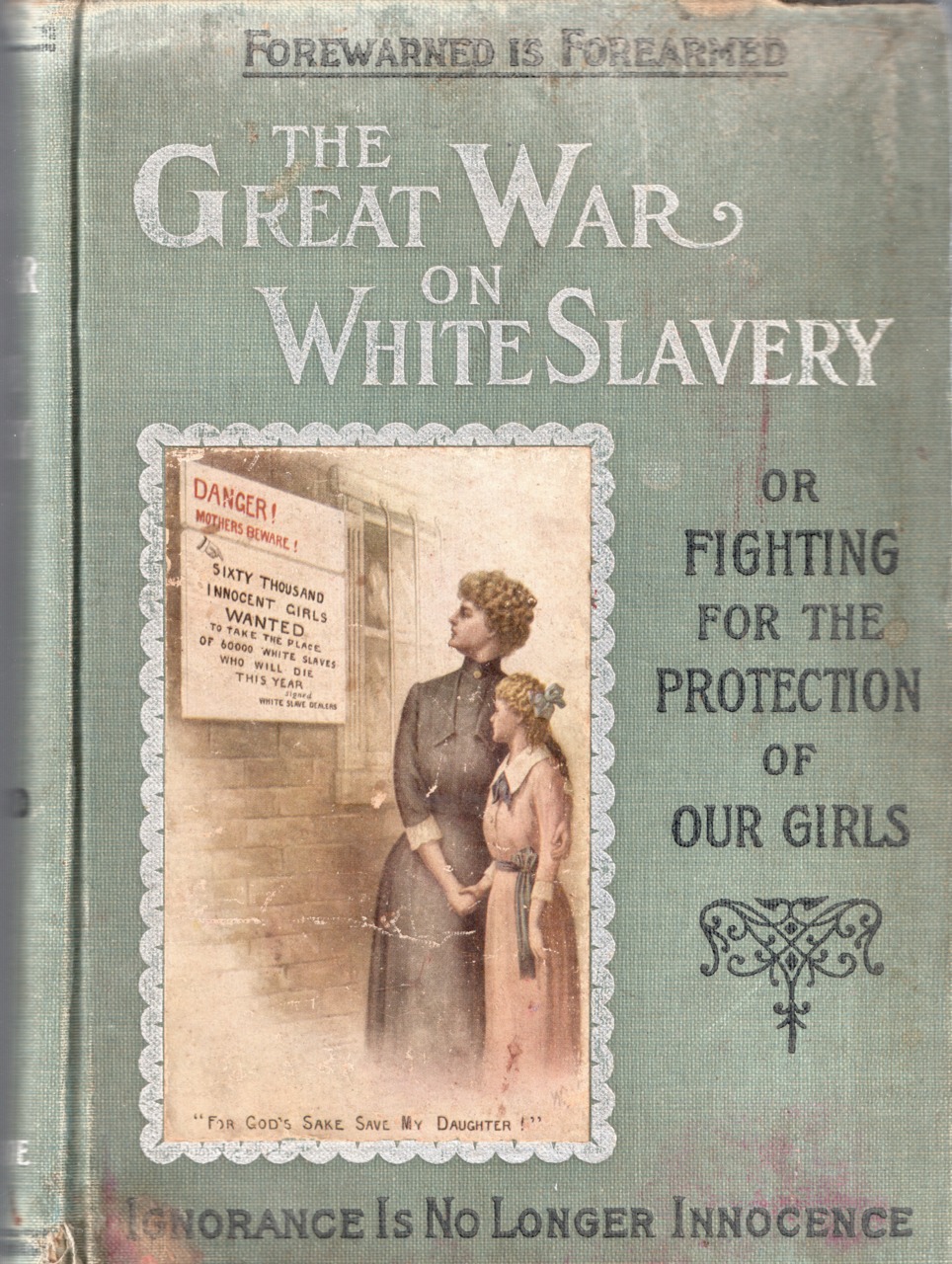

By the time of Barrett’s appointment in 1914, human trafficking – or as it was referred to then, white slavery – had become well-publicized across the U.S. This notoriety was spurred by a high profile grand jury inquiry in New York City led by the philanthropist John D. Rockefeller Jr., who also bankrolled the investigation. According to its final report, the grand jury had called to testify “every person we could identify who we had reason to believe might have information on the subject.” The grand jury found sufficient evidence to call for a concerted effort to eradicate trafficking, and Rockefeller established a fund to assist victims. His efforts were joined by numerous groups that sought to address the issue in America. The early efforts were chronicled in books by Illinois prosecutor Clifford Roe like the “Great War on White Slavery.” In his “Prodigal Daughter: The White Slave Evil and the Remedy,” published in 1911, Roe included “special articles” from individuals working with the “fallen women” or victims of slavery.

The issue was sensationalized by the nascent film industry. These early movies were epitomized by “Traffic in Souls,” which debuted in 1913 and was broadly released across the U.S. The filmmaker, the Universal Film Corporation, purported the picture to be based “on actual reports of the Rockefeller Investigating Committee.” In addition to its large production costs ($25,000, which made it the most expensive at that time), its publicity budget included newspaper ads and movie screenings that were also frequently accompanied by lectures designed to spur action.

Kate Waller Barrett’s interest in trafficking stemmed from her work as president of the Florence Crittenton Mission, an organization that had also provided information to the Rockefeller grand jury. The mission attempted to assist girls and women who had been exploited for sex, were homeless or abandoned, who had immigrated to this country with no U.S. contacts, or who were forced into “unsavory” circumstances. As early as 1896, Barrett had noted in an address to the International Christian Endeavor Convention, that the plight of those “white slaves” is the “swiftly succeeding steps of the brothel, the jail, the hospital and the potter’s field.” In the same address, Barrett estimated that these steps took “only five years.” As she became more involved in the cause, she grew concerned about what happened to those women who were exploited and then deported.

On Aug. 18, 1913, she wrote to Anthony Caminetti, U.S. commissioner general of immigration, to determine the “modus operandi” related to those girls and women deported for reasons of immorality. Barrett’s letter appears only as a request for information, although she does inform the commissioner that both the Crittenden Mission and the National Council of Women of the United States have been concerned about the plight of these women and sought to help them.

At first the Bureau of Immigration responded with an explanation of the process and a statement of how the bureau’s actions were limited by policy and law. Assistant Commissioner F.H. Larned responded to Barrett that foreign governments were notified of the deportation of alien prostitutes and the responsibility of the bureau ceased after delivery on board ship at the port of embarkation. He also assured Barrett that “no publicity [is] attached to the proceedings in the United States other than that which may accrue through the summoning of witnesses, etc., and this office strives to reduce this to the minimum.”

Soon the bureau determined that Barrett could assist in both the prevention of human trafficking and the reduction of its aftermath through her national and international connections with non-government organizations, especially in her role as president of the National Council of Women in the United States. The commissioner later summarized the value of Barrett in a memorandum for the secretary of labor that also sought an extension of her position as special agent of the bureau:

Heretofore the organizations and societies of women in this country (and of course also those abroad) have hesitated to undertake any active cooperation with the Bureau of Immigration in the deportation of immoral women and girls, for the reason, doubtless, that they have felt that a serious hardship was visited upon such aliens in which they were likely to fare worse than here and in which their chance of reformation would be reduced instead of increased. By getting the American societies over which Mrs. Barrett presides interested in our work, and through them the similar and related societies abroad, ... a feeling is being produced that the provisions of the immigration law can be carried out with the intended benefit to this country, with the danger of the further degradation of the aliens reduced to a minimum ...Moreover, by this system of cooperation it is hoped and believed much better results will eventually be attained in the apprehension of the real culprits – those responsible for the original downfall or continued immorality of the women or girls.

Barrett’s position as a special agent gave her broad latitude and took her to Europe. As noted in her 1914 published report to the commissioner general, she was charged with fact-finding, conferring with representatives of foreign governments and even negotiating agreements as “would assist the Department of Labor in right solving some of the problems growing out of the white-slave traffic.”

Barrett used every part of her trip to execute her charge. She even selected to travel on the ship Canada as part of her international fact-finding mission. She had determined that the ship was carrying a number of women deportees on the same voyage. She also knew that on its earlier trip to the U.S. that it carried women who were refused entry into the country because they were suspected of immorality.

By sailing on the Canada, she believed that she could determine how these individuals were treated while on board, what safeguards were on board to prevent them from being exploited while en route and what happened to the women once they disembarked.

She was also a delegate to the Quinquennial Meeting of the International Women’s Council in 1914 and was scheduled to address the subject of white slavery before its delegates. Her designation as a special agent for the Bureau of Immigration enabled her to bring a proposal for international cooperation to the council from the U.S. government. Barrett was successful in her efforts as reported in the final report of the meeting. The international council directed each national council to “correspond with the United States Government” on issues related to human trafficking. It also called on each national council to ask its government to “unite in an international conference of immigration officials” on these issues.

Barrett returned to the U.S. with a wide-ranging understanding of the issues relating to international human trafficking and the real promise of international cooperation. Unfortunately the outbreak of World War I in July 1914 hampered international progress. But Barrett’s work with the bureau continued, and she had a profound effect on how immigrant women were treated while in U.S. custody and on elevating the status of women who worked for the bureau.

Throughout 1914 the bureau focused on establishing procedures that governed the treatment of women in custody. To help develop the procedures and the required partnerships with charitable organizations, the commissioner general extended Barrett’s appointment. For continuing her work, she was paid $100 a month. The work involved amending rule 22, which governed women and girl detainees.

In most locations, neither the bureau nor the law enforcement facilities that it worked with had adequate facilities or staff to accommodate detained females. Both the commissioner general and Labor Secretary William B. Wilson advocated partnering with charitable organizations for the housing of female detainees until their cases were adjudicated. This was a substantial procedural change across the bureau. The Florence Crittenton Mission was to play a major role in housing detainees and the commissioner general requested from Barrett “a list giving location and address of matrons of your missions in the United States so that we may forward a copy of said rule [22] to each.”

As first proposed, this amendment placed female detainees in the care and supervision of the missions while their cases were reviewed. This new policy faced considerable resistance from the regional offices. Most cited fear of flight of the detainees and convincingly argued that the policy interrupted the chain of custody. A letter from Charles Seaman, inspector in charge in Minneapolis, to the national office summarized this argument.

... charitable homes ... have no legal right to hold a girl against her will. Therefore, in accepting a girl or woman for this service the responsibility rests on the office ... In as much as there are no woman employees at this station, I will be unable to comply herewith.

Barrett used this argument to advance the position of women employees in the bureau. As a special agent with access to both the labor secretary and commissioner general of immigration, she was able to argue that women detainees should be handled by female employees. And the bureau listened. But Waller’s advocacy went further and sought the designation of special officer for these women employees.

This policy change requiring women staff to be responsible for female detainees sent the national and local offices scrambling to find appropriate staff. The records of the bureau at the National Archives attest to that. A handwritten note in the commissioner general’s official correspondence also indicates Waller’s influence on this decision. In seeking to identify female employees to serve in this role, the commissioner general wrote, “Prepare same letter to all stations in re KWB where there are woman employees in any capacity except charwomen.” The letter went to commissioners of immigration and inspectors in charge of districts. Because of Barrett, women across the bureau were going to receive title changes. The letter stated:

... the female employees already designated at a number of the stations to give particular attention to the cases of arrested women and girls will hereafter be known as “special officers,” and they are accordingly so designated at this time.

The offices responded, some reluctantly, and others worried that just the association of female staff with women of ”questionable morality” would be detrimental to staff. Most offices simply nominated the only woman on staff. Assistant Commissioner of Immigrations Louis Hoffmann’s response to the commissioner general is typical. He wrote of the woman designated as special officer that, “Her name, of course, is the only one I can submit, and while she is an unmarried woman and has had no experience in such a line, she could attend to special work of that character along with the performance of her ordinary duties.”

Barrett was very involved both in determining how female detainees were treated and in outlining the role of female employees in the conduct of their cases. This is illustrated in a memorandum she penned “in regard to instruction to be issued to women officers selected for the care of deported women and girls.” In the memo, Waller stated that female officers were not just to oversee the detainees care and welfare. They also were to be investigators that advised the bureau. Barrett wrote:

On the completion of such an investigation the woman officer is to write a complete report of the case, making such recommendations for the final disposition of the case ... This report and other recommendations are to be sent with all other documents pertaining to the case to the Commissioner General’s Office.

Once the revised rule was put in place, the bureau drafted a circular, or printed directive, that outlined the bureau’s new policy and procedures. Wilson sent Barrett a copy and acknowledged Barrett’s contribution in his cover letter:

Enclosed please a find proof-sheet of a circular now being issued by the Department as a means of placing in concrete shape and in definite regulations the practices which have already resulted from the new methods of handling cases of arrested women and girls, in the inauguration of which you so actively and effectively participated.

The issuance of the circular and the protocol for the handling of female detainees was covered in the nation’s newspapers, prompting interest from other nations. A letter to the bureau from the Belgian Bureau illustrates the interest. The letter requests a copy of the circular and asks for “further details of your plan for assisting immigrant women of which I saw an account in an evening paper this week.” The Labor Department also sent 425 copies to the State Department for distribution.

Barrett’s work clearly marks a milestone with her own appointment as special agent and her impact on the policies and procedures of the bureau. Not only did she change the way women were treated while in U.S. custody, but she also introduced a means in which female employees stood beside their male counterparts as officers of immigration.

Barrett’s work continued beyond the revision of rule 22. She continued to serve the bureau by investigating situations where human trafficking was prevalent. In 1915 she was dispatched to the Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco because international fairs and expositions often attracted prostitution rings that exploited immigrant females. The bureau empowered Barrett “to arrange and put in place a plan” to address trafficking and assist its victims. In so doing, Caminetti further advanced the role of women in executing the responsibilities of the bureau. He wrote Charles C. Moore, president of the Panama-Pacific Exposition, to introduce Barrett as “a special agent of the Department of Labor in connection with the Immigration Service” as the coordinator of the bureau’s efforts against trafficking at the exposition. Within the bureau, both Wilson and Caminetti ensured the San Francisco office supported her efforts.