Around the Agency

Jacksonville, Florida

operations San Francisco, California

Jacksonville, Florida

Three CBP women receive federal law enforcement awards

Trio honored during group’s annual meeting in California

By John Davis

Women in Federal Law Enforcement, a nonprofit that advocates for gender equity in federal law enforcement, recognized three members of U.S. Customs and Border Protection for prestigious national awards. They received the honors during the group’s annual leadership training conference in Rancho Mirage, California, June 25-28.

Debora Hall, an aviation enforcement agent with CBP’s Jacksonville, Florida, Air and Marine Branch, received the group’s 2018 Outstanding Federal Law Enforcement Employee award. Hall, the only female agent assigned to the 60-person branch, helped save lives and provided thousands with relief during Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria.

Jennifer Bradshaw, the area port director also in Jacksonville, garnered the Julie Y. Cross Award, recognizing her work as the deputy area commander overseeing emergency response efforts last September and October in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands during Hurricanes Irma and Maria.

Leticia Romero, assistant director for field operations in San Francisco, was tapped for the group’s Public Service Recognition Award for her contributions related to significant interdictions including some of the largest narcotics seizures made in the history of the Port of San Francisco.

Todd Owen, CBP’s executive assistant commissioner of field operations, pointed to his agency’s commitment to hiring women in its workforce.

“When you look at our recruitment and the onboarding that we’ve done in the last three years, over 25 percent of our new hires are females,” he said, pointing out how the Office of Field Operations has more than 24,000 sworn officers, 18 percent of which are female, higher than the rest of federal government’s average of 14 percent.

“Leadership truly matters, and if we’re going to be effective in meeting the mission that we face every single day, we need the right people in the right positions,” explained Owen. “I think events like this… go an incredibly long way to help develop the future leaders of tomorrow.”

CBP’s fentanyl strategy brings agencies together

By Paul Koscak

Two.

That’s how many pounds of fentanyl CBP seized in 2013.

In 2017, 1,476 pounds.

Soaring addict demand fed by transnational criminal organizations and easy access has made fentanyl the leading cause of overdose deaths in the U.S., killing more than 20,000 people last year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, challenging law enforcement, social service and healthcare providers.

With e-commerce, the neighborhood drug pusher is no longer needed to get a fix. Fentanyl—a synthetic opioid—can be ordered online and shipped to any doorstep. Moreover, fentanyl is lightweight and sent in small parcels making the drug tough to detect.

The unprecedented opioid addiction and overdoses has even involved the White House, prompting President Trump to declare the crisis “a national health emergency.”

While these factors have elevated fentanyl to the forefront of drug abuse, the substance has been in demand for more than a decade beginning with overprescribed addictive painkillers and is now nearly everywhere.

“In recent years the misuse of controlled prescription drugs and the growing use of heroin, fentanyl, and fentanyl analogues has spread into suburban and rural communities growing across socioeconomic classes, age groups, and races.” said Roland Suliveras, the director of CBP’s National Targeting Center’s Cargo Division. Located just outside Washington, D.C. in Virginia, the center identifies travelers and cargo that pose risks to U.S. security including terrorists, illegal migrants, along with illicit goods and drugs.

Opioid prescriptions shot up from 76 million in 1991 to 207 million in 2013, according to a Department of Homeland Security assessment of the latest data. Moreover, the U.S. consumes nearly 100 percent of the world’s Vicodin and 81 percent of Percocet.

In the past, fentanyl was obtained through pharmacy theft, phony prescriptions or illicitly sold by patients, doctors and pharmacists. Now, it’s mostly smuggled into the United States as a powder.

Fentanyl trafficked across the Southwest border is sometimes combined with other narcotics such as heroin, cocaine, and meth, but it’s only about 10 percent pure. Mail shipments, usually from China, can be up to 90 percent pure, said Manny Garza, CBP’s director of manifest and conveyance security. Because high potency is deadly, smugglers mix the fentanyl with lactose and press them into thousands of tablets, “pill mills in someone’s kitchen” as he describes it.

In fiscal 2017, CBP processed a half-billion international mail shipments arriving in the U.S.,” said Garza. “How do you inspect a million parcels per day?” Nevertheless, seizures are high because of increased training and awareness, he pointed out.

In response, CBP moved forward to bring together domestic and international law enforcement and governments along with other stakeholders into a single force to combat the scourge. Outlined in the CBP strategy that targets opioids, the approach is an overarching plan for those entities to work together, share intelligence, and target the supply chain. The strategy also highlights safety for officers and Border Patrol agents on the frontline and others at risk to opioid exposure.

“CBP will strengthen our federal, state, local, tribal, commercial and international partnerships to combat opioids,” said Commissioner Kevin McAleenan, in describing the alliance. “We will work alongside law enforcement, postal, legislative and executive branch offices to meet this crisis head on and relentlessly target and interdict the transnational organizations and individuals producing and trading these poisons.”

Led by CBP’s National Targeting Center, the strategy is already making headway.

CBP signed a memorandum with the U.S. Postal Service to target suspicious parcels and for the first time postal service representatives work at the center. In addition, a new electronic system that targets and automatically shares data on suspicious mail is giving postal systems the ability to disrupt fentanyl shipments. Thirty-eight foreign postal operators including China, Hong Kong and Canada participate in the system. Before the strategy, just 23, said Amy Schapiro, CBP’s risk analysis and decision support branch chief who helped write the strategy.

“E-commerce has changed the drug market,” she said. “The magnitude of the mail is hard to believe. It sometimes feels like a losing battle.” Still, the Office of Field Operations made 437 fentanyl seizures in fiscal 2018, a 126 percent increase from the 346 seizures in fiscal 2017.

As the only agency in the U.S. that can perform pollen analysis, CBP helped the Nebraska State Patrol locate the origin of a kilo of fentanyl it seized.

According to the results, “it was from China,” Schapiro said. In November, 2017, CBP was the first agency to train its K-9s to detect fentanyl.

Following the strategy’s emphasis on communication and outreach, CBP held a weeklong fentanyl and opioid conference in June. The event drew a wide variety of law enforcement officers from across the country and internationally. They included Homeland Security Investigators from Cleveland, Houston and Beijing; drug enforcement agents from India and Thailand; members of the Justice Department, the FBI, the U.S. Postal Service; and representatives from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence and the White House’s Office of National Drug Control Policy.

Participants networked and shared challenges facing their agencies. E-commerce dominated many of the discussions.

“Today you don’t need to be a car thief or commit robbery to pay for your habit,” said Michael Grote, a Homeland Security Investigations special agent from Brooklyn Heights, Ohio. He also explained how traffickers make money just by repackaging a fentanyl order and resending it for a profit.

FBI Supervisory Special Agent Christopher Brest had perhaps the most intriguing presentation about the dark web. The dark web requires special software to access and contains a world of illicit trade, particularly in narcotics.

Brest showed an organization chart of a typical dark web drug trafficking outfit with a structure that looked more like a Wall Street corporation. The criminals are organized into departments (It even had a public affairs department!) all reporting to an administrator.

The dark web is difficult to shut down or even locate because servers are mostly overseas. Communications are encrypted and anonymous and payments are in bitcoin making the supply chain difficult to trace, he said.

Nevertheless, collaboration can go a long way in disrupting the supply chain.

In May, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, with assistance from CBP and Homeland Security Investigations arrested a group of traffickers in Toronto who sold a variety of drugs through the dark web, including fentanyl, heroin and cocaine. CBP intercepted fentanyl shipments connected to the traffickers and the investigators provided photographic evidence, explained Suzanne Elkander, a Canada Border Services Agency agent who’s assigned to the National Targeting Center.

“It’s amazing what four people and a computer can do,” she said.

The group is believed to have made several thousand illegal drug transactions throughout the world paid by bitcoin and then shipped to customers using the regular mail.

CBP worked with the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration in seizing sophisticated pill press machines that arrived at the Long Beach California, port of entry. The machines make pills that look like prescription medications and will be held until an investigation can show they have proper registration, otherwise they’re illegal. Some presses can produce nearly 170,000 pills per minute, said Assistant Port Director Cheryl Davies who heads the port’s anti-terrorism contraband team.

In another joint operation, two Chinese nationals who sold and manufactured fentanyl throughout the U.S. were indicted after an investigation by the Justice Department. One of them operated at least two chemical plants in China that produced tons of fentanyl and fentanyl equivalents. CBP, along with the Ministry of Public Security of China provided “valuable investigative assistance,” according to the Justice Department.

CBP is part of the DEA Special Operations Division in Chantilly, Virginia, an interagency group that works internationally to combat drug traffickers and played a crucial role in the two indictments, said Leonard Le Vine, a trial attorney with the U.S. Justice Department’s Narcotics and Dangerous Drug Section. “By having CBP embedded, we can look at shipments and target what’s coming and going and link it to the suspects,” he said. “CBP is a vital and integral part of what we do.”

Operation Opioid Counter Strike

By John Davis, Photos by Scot Osborne

The scourge of opioids is killing 115 Americans every day. Last October, President Donald Trump declared the crisis a national health emergency, pledging the full support of the federal government in this fight. Part of that fight includes U.S. Customs and Border Protection stopping opioids at the border and ports of entry. A key part of that effort is CBP’s participation in the Joint Task Force-West coordinated Operation Opioid Counter Strike, a nationwide collaboration using many Department of Homeland Security assets – CBP, including Border Patrol, Air and Marine Operations, and Field Operations; Homeland Security Investigations; Immigration and Customs Enforcement; and the Coast Guard – to decrease the flow of opioids into the country. The operation looks to break up the criminal organizations that produce and smuggle the drugs in the first place, while also educating those in federal law enforcement about opioid dangers.

The border areas in California, Arizona, New Mexico/West Texas and South Texas are prime areas for the smuggling of opioids, and other illicit cross-border activities. CBP plays a vital role in this fight through its contribution within the group, headquartered in San Antonio.

Joint Task Force-West coordinates the multi-agency effort with federal, state, local, tribal and international partners along the southwest border to prioritize threats and conduct intelligence-driven counter-network operations to disrupt and dismantle criminal and illicit networks undermining border security.

The photos on these pages highlight some of the opioid busts CBP contributed to the operation.

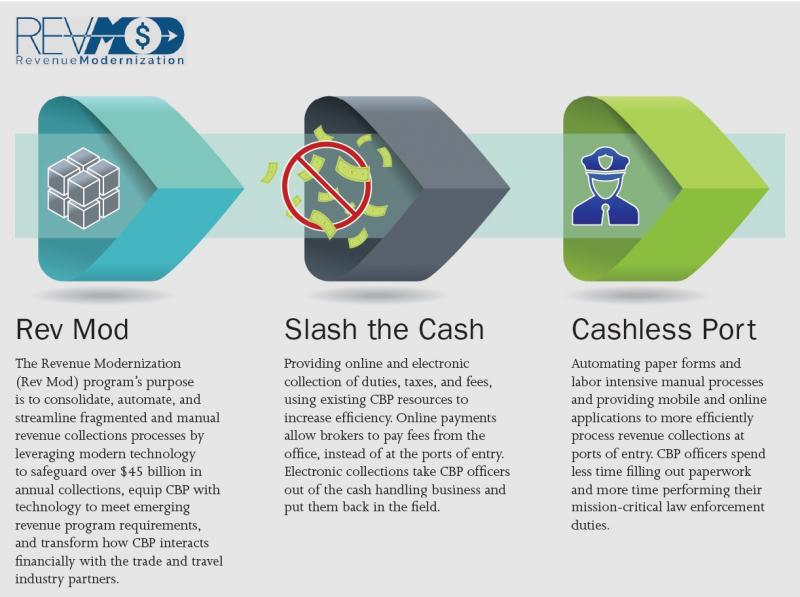

Revenue Modernization efforts move CBP’s collections into the future

By Rebecca Chisholm

A new system of collecting fees at ports of entry is helping U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers collect those revenues more efficiently, saving time and resources for the U.S. government and commercial businesses. Mobile Collections and Receipts, part of the larger CBP Revenue Modernization program, uses re-engineered business processes and automation to eliminate the need for paper-based collection forms and receipts at seaports. A tablet-based application lets CBP officers track and collect maritime arrival fees electronically and provide electronically-generated and emailed receipts. Four ports of entry are currently using the technology, with an expanded roll-out expected in the near future.

“It’s been a very positive response, from not only the boots-on-the-ground frontline officers, but the managers as well,” said LaFonda Sutton-Burke, port director at the Los Angeles/Long Beach Seaport.

The benefits of Mobile Collections and Receipts are noticeable. Between April 2017 and April 2018, the new technology reduced the average vessel processing time from 17 minutes to 11 minutes, saving nearly 350 hours of CBP officer time annually. As of April 2018, there were over 8,500 electronic receipts issued and $15.5 million dollars collected through the system.

Sutton-Burke also looks forward to future upgrades and additional functionality. “We are ecstatic about it. It’s a transformational initiative that’s pulling us further into the 21st century.”

Another important Revenue Modernization pilot project is the Smart Safe technology. With features comparable to a miniature bank, Smart Safe allows CBP officers to spend less time counting and reconciling cash and coins, allowing them to redirect those hours toward mission-critical law enforcement duties. Currently, the ports of Blaine, Washington, and Brownsville, Texas, are piloting the use of Smart Safe technology to reduce cash-handling activities.

Michelle Sanchez, supervisory entry specialist at the Port of Brownsville, was pleasantly surprised by ease of the Smart Safes’ learning curve. “Our biggest challenge was training because of how shifts rotate. I thought getting all the supervisors trained would be difficult, but once they used it once or twice, they were good to go. It’s pretty simple and user friendly.”

Sanchez is most impressed with how much time using a Smart Safe has saved the port. Results from the pilot ports found an 83 percent reduction in time spent on seizures, from nearly 40 minutes to under 7 minutes, as well as a more than 70 percent reduction in time spent on end-of-day reconciliations, from more than three-and-a-half hours to just more than an hour.

In addition to physical technologies, Revenue Modernization includes an Online Payment Options pilot project, which is working to update the way a number of different fees are paid. Most notably, CBP’s Office of Trade worked with the Revenue Modernization program to promote the addition of online payments and submissions for Triennial Broker Reports and Fees, a status report and $100 fee all broker license holders are required to file every three years. The change eliminates the need for customs brokers to file directly with the port that issued their license.

CBP officials are promoting submission and payment of these fees on Pay.gov, a secure, online payment system for the public to pay federal government agencies. About 80 percent of brokers successfully used the Pay.gov option in 2018, and the results were positive.

“I like that it’s going online, I think that there’s an opportunity to make things less labor intensive,” said Brian Barber, director of U.S. brokerage operations and regulatory affairs at Wilson International. “It’s been a great process.” Barber is encouraged by the increased ability for brokers to pay online. “Moving some of the payments to Pay.gov will be helpful in the long term. Electronic is definitely the way we want to go in the future.”

of shipping containers as they inspect incoming cargo at the Port of Miami in Miami, Florida. Photo by Glenn Fawcett

The larger Revenue Modernization efforts came at the request of people in CBP’s Revenue division in the Office of Finance.

“They made comments like, ‘We haven’t had an update to our systems since Ronald Reagan was in office!’” said Kathleen Druitt, Program Manager of the Revenue Modernization program and Director of the Financial Solutions Program Management Office.

At the same time, Chief Financial Officer leadership wanted to find a way for CBP to improve its ability to report on the revenue collections data while enabling CBP officers to spend less time on collections and more time in the field. “CBP took that story to DHS/CBP leadership and the Office of Management and Budget, who heard our pleas and saw how modernization could reduce CBP officers’ collections-related work at the ports,” said Druitt.

Druitt added that while Revenue Modernization won’t achieve a completely cashless port, CBP is still heading in that direction in the same way much of modern U.S. commerce has moved away from cash and toward electronic and online payments.

“If the law did not require that we accept paper cash (as well as silver and gold), we would eliminate cash as a payment option,” said Druitt. “However, our Revenue Modernization program will continue to deliver capabilities to move CBP toward our goal: ‘Slash the Cash - Toward a Cashless Port.’”